|

Lyman Frank Baum (who published under

the name L. Frank Baum) was born in New York in 1856.

He began his career at the age of 25 by writing for

musical theater; he was also an actor. Baum eventually

turned to journalism, and moved to Chicago in 1891,

writing for the "Evening Post." To earn extra

money, he also sold porcelain and china; you will see

evidence of that in the stories he tells in Wonderful

Wizard of Oz. In 1897 he published Mother Goose in Prose,

followed by Father Goose in 1899. Based on the success

of this book, he was able to give up his other jobs

and devote himself full-time to writing. Lyman Frank Baum (who published under

the name L. Frank Baum) was born in New York in 1856.

He began his career at the age of 25 by writing for

musical theater; he was also an actor. Baum eventually

turned to journalism, and moved to Chicago in 1891,

writing for the "Evening Post." To earn extra

money, he also sold porcelain and china; you will see

evidence of that in the stories he tells in Wonderful

Wizard of Oz. In 1897 he published Mother Goose in Prose,

followed by Father Goose in 1899. Based on the success

of this book, he was able to give up his other jobs

and devote himself full-time to writing.

And in 1900 he published The Wonderful

Wizard of Oz. The book was a bestseller, and Baum immediately

created a musical stage version which successfully appeared

on Broadway and toured the country for ten years, from

1902-1911. (None of the songs from the theater musical

were later used in the musical film starting Judy Garland.)

In 1904, Baum published a next installment:

The Marvelous Land of Oz: The Further Adventures of

the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman. He went on to write

a total of fourteen books set in Oz, with a varying

cast of characters.

In 1910, Baum and his family moved to

Hollywood, California. He founded the Oz Film Manufacturing

Company and began making films based on the Oz books.

The problem was that back in the early years of the

century, nobody had really started making films for

children. Baum found it difficult to market the films,

and they were not financially successful. But Baum continued

to produce the Oz books, publishing a new book every

year until his death in 1919, just a few days before

his 63rd birthday.

After Baum's death, other authors -

notably Ruth Plumly Thompson - continued to produce

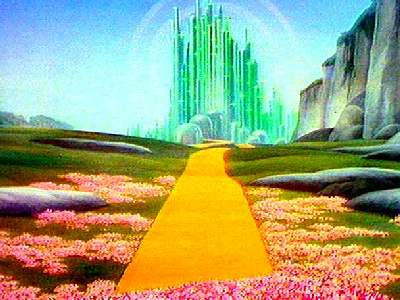

books for the Oz series. And in 1939, Warner Brothers

released the Victor Fleming musical starring Judy Garland,

under the title The Wizard of Oz. This film became an

icon of American cinema, and most people now know the

version of the Oz story presented in that film, rather

than the story told by Baum. Fortunately, unlike many

Disney productions of children's classics, the Wizard

of Oz is amazingly faithful to Baum's original book.

You will see some of the most important differences

in the reading this week: Dorothy's shoes are not red,

and the Emerald City is not actually green, and the

whole trip to Oz is real - it is not a dream, as in

the movie. Plus there are many adventures in the book

which had to be left out of the movie, while the movie

added more to the frametale, describing Dorothy's life

in Kansas, creating the characters Hunk, Zeke, Hickory,

Professor Marvel and Miss Gulch, who are all counterparts

to characters in Oz. These Kansas characters are not

part of Baum's original story.

Because all of Baum's Oz books were

published before 1923, they are in the public domain.

This means that you will find plentiful copies of all

of these texts on the Internet, although only two books

- the Wonderful Wizard of Oz and the sequel The Marvelous

Land of Oz are available in illustrated editions online.

There are many rumors and legends associated

with the Oz books, and with the film. One of the most

interesting has to do with where the name Oz comes from.

There are many conjectures about that, and Baum himself

promoted this charming explanation in a book introduction

in 1903:

I have a little cabinet letter file

on my desk that is just in front of me. I was thinking

and wondering about a title for the story, and had settled

on the "Wizard" as part of it. My gaze was

caught by the gilt letters on the three drawers of the

cabinet. The first was A-G; the next drawer was labeled

H-N; and on the last were the letters O-Z. And "Oz"

it at once became.

Of course, it is entirely possible that

Baum himself was making that story up. Other theories

abound. Martin Gardner's theory ("Mathematical

Games," in Scientific American. February 1972)

is that the name OZ is derived from the abbreviation

NY, Baum's home state, with each letter moved up one

place in the alphabet (like the computer HAL in 2001:

A Space Odyssey having the name IBM, with the letters

moved one back in the alphabet).

One of the more persistent legends about

the filming of the Wizard of Oz musical is that an actor

playing one of the munchkins, "driven to despair

over his unrequited love for a female munchkin,"

committed suicide during the shooting of the film. You

can allegedly seen the hanged munchkin in the scene

where Dorothy and the Scarecrow are gathering apples

from the angry apple trees. Like most grisly urban legends,

the story of the suicidal munchkin is not true. Apparently

there were some peacocks roaming the set, and one of

them spread its wings vaguely in view of the camera,

creating the strange effect that has been interpreted

as the dangling munchkin. Given the enormous popularity

of this movie, there is a lot of Wizard of Oz Movie

Trivia.

One of the most interesting legends

associated with Baum's book, The Wonderful Wizard of

Oz, is that it is actually a closely argued political

allegory in support of "The Radical Free Silverites,"

a Democratic populist movement in America in the late

19th century. To alleviate the effects of an economic

depression in the 1890's, some politicians were arguing

for augmenting the monetary gold standard with silver

coinage. This platform is most closely associated with

William Jennings Bryan, who was the Democratic candidate

for President in 1896. You probably read about his "Cross

of Gold" speech in your U.S. history class, when

Bryan demanded the abandonment of the strict gold standard

in order to bring relief to the working classes of America:

"You shall not press down upon the brow of labor

this crown of thorns, you shall not crucify mankind

upon a cross of gold." Baum was a lifelong Democrat

and supporter of populist politics.

So, what does this have to do with Oz?

You will find out that Dorothy does not have ruby slippers

in the book; her slippers are silver. Meanwhile, the

road to Oz is paved with gold. Here is how Mark Lovewell

summarizes the allegorical theory of the metals:

Dorothy, the heroine, symbolizes mid-America

at its best -- honest and open-hearted. Uprooted by

a tornado, she is enticed to follow a yellow brick road

to the fantasy-land of Oz (an ounce of gold). The Scarecrow

she meets symbolizes the Western farmer who thinks he

has no brain but turns out to be more capable and intelligent

than he realizes. The Tin Woodman who joins them represents

the American worker whose grinding labours have left

him, at least for a time, rusted and heartless. And

the Cowardly Lion who tags along depicts none other

than William Jennings Bryan, the leader whose lack of

courage finally caused him to betray the pro-silver

cause. [...] Dorothy is then able to return to the security

of home by clicking her silver (not ruby, as in the

movie) slippers.

According to this theory, Oz is not

a fanciful name made up based on the letters on a filing

cabinet: it is the abbreviation for "ounce."

In any case, whether Baum was inspired

to write a political allegory, or whether politics were

the farthest thing from his mind at the time, the final

result is a classic of children's literature. I'm guessing

that probably everyone who is doing this unit has seen

the musical film version. You will find this week that

the book has a different and special charm all its own.

In the original story, Dorothy is swept

away from Kansas in a tornado and arrives in a mysterious

land inhabited by "little people." Her landing

kills the Wicked Witch of the East (bankers and capitalists),

who "kept the munchkin people in bondage."

In the movie, Dorothy begins her journey

through the Land of Oz wearing ruby slippers, but in

the original story Dorothy's magical slippers are silver

[a reference to the bimetallic monetary system advocated

by W.J. Bryan]. Along the way on the yellow brick (gold)

road, she meets a Tin Woodsman who is "rusted solid"

(a reference to the industrial factories shut down during

the depression of 1893). The Tin Woodsman's real problem,

however, is that he doesn't have a heart (the result

of dehumanizing work in the factory that turned men

into machines?).

Farther down the road Dorothy meets

the Scarecrow, who is without a brain (the farmer, Baum

suggests, doesn't have enough brains to recognize what

his political interests are). Next, Dorothy meets the

Cowardly Lion, an animal in need of courage (Bryan,

with a loud roar but little else). Together they go

off to Emerald City (Washington) in search of what the

wonderful Wizard of Oz (the President) might give them.

When they finally get to Emerald City

and meet the Wizard, he, like all good politicians,

appears to be whatever people wish to see in him. He

also plays on their fears... But soon the Wizard is

revealed to be a fraud—only a little old man "with

a wrinkled face" who admits that he's been "making

believe."

"I am just a common man,"

he says. But he is a common man who can rule only by

deceiving the people into thinking that he is more than

he really is.

"You're a humbug," shouts

the Scarecrow, and this is the core of Baum's message.

Those forces that keep the farmer and worker down are

manipulated by frauds who rule by deception and trickery;

the President is powerful only as long as he is able

to manipulate images and fool the people.

Finally, to save her friends, Dorothy

"melts" the Wicked Witch of the West (just

as evil as the East), and the Wizard flies off in a

hot-air balloon to a new life. The Scarecrow (farmer)

is left in charge of Oz, and the Tin Woodsman is left

to rule the East. This populist dream of the farmer

and worker gaining political power was never to come

true, and Baum seems to recognize this by sending the

Cowardly Lion back into the forest, a recognition of

Bryan's retreat from national politics.

Dorothy is able to return to her home

with the aid of her magical silver shoes (Ruby shoes

in the movie), but on waking in Kansas, she realizes

that they've fallen off, representing the demise of

the silver coinage issue in American politics.

Regardless of the true nature of the

message in Baum's story, it is a true classic, and my

niece and nephews did a fine job of entertaining us

in their recent

school production of the original.

|